A Review of Tiffany Morris’s Green Fuse Burning

By Zachary Gillan

Trauma, in Tiffany Morris’s recently published Green Fuse Burning, is written not only into the body, but into the land itself. The weird place—one of my favorite mainstays of Weird fiction—is a way for horror and unsettlement to seep in through a landscape haunted or otherwise tainted, and this ecohorror novella invokes the weird place in exceptional ways. Just as Morris’s protagonist, Rita Francis, mourns the recent loss of her father, grief also suffuses the land in the form of colonization and the genocide of Native people (Morris, like Rita, is of dual Mi’kmaq/settler heritage), as well as in the the form of climate change wreaking havoc on the world. Colonization becomes a useful grounding for the horror happening here—grief, colonialism, and climate change all settling into and maliciously disrupting the order of things. One might even say that Green Fuse Burning, in some ways, is a radical reinvention of the awful horror trope of the Indian burial ground. It’s a surreal, beautiful nightmare, too, that tackles its dark subject matter with urgency and power.

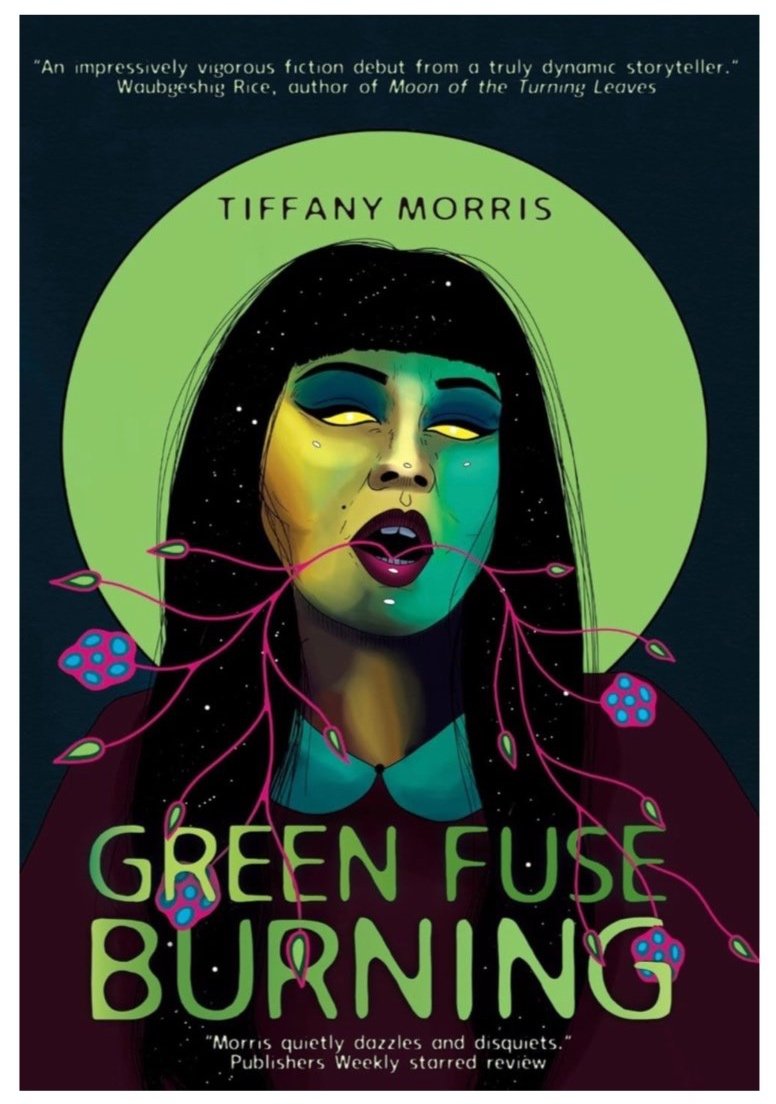

Cover Art by Chief Lady Bird, Cover Design by Selena Middleton

The weird place in question is a swamp in the ancestral lands of the Mi’kmaq, where Rita is secluded in an artist’s retreat, while strange things are afoot outside her cabin. Morris’s book is structured around a collection of its protagonist’s paintings, Devastation of Light: The Recovered Paintings of Rita Francis, a collection that’s recovered only after the artist’s disappearance (weird art—I have to say it—is another of my favorite commonplaces of Weird fiction). Each of the novella’s six sections opens with exhibition text describing one of Rita’s paintings, and Morris nails the critical voice necessary to make these feel real—not unlike how she expertly handles the praxis of foreshadowing and inspiration that interweaves between the painting and the events of the chapter feeding into it. Speaking to Morris’s portrayal of the artist herself, Rita is locked in an unproductive state and depressive fugue following both the death of her Mi’kmaq father, from whom she had been unwillingly estranged, and the symbolic death of her relationship with her mother, a white abuser with whom she had never been as estranged as she should have been. She’s also trapped in a dead-end relationship with ex-artist Molly, a white, MLM-espousing party girl whose thin portrayal is one of the book’s only weaknesses. It’s Molly who secures the fellowship behind Rita’s back, setting the novella in play.

Morris is a poet in addition to a writer of prose, and her meticulous word choice, flow, and use of language embody and give shape to Green Fuse Burning. On the first page of Rita’s narrative, when the character is awoken by sounds outside of the cabin and immediately assumes someone is moving a body, Morris describes: “A limp assembly of limbs, heavy with the absence of story. Of course. It had to be a body. Rita shut her eyes tight. It couldn’t be held off; the memory was a wave destined to crash over her.” The beautifully catching almost-repetition of “limp” and “limbs,” and the immediate link with physicality and emotional trauma, are characteristic. Particularly striking is Morris’s precision regarding Rita’s physicality, and the intersections between her trauma, her history with therapy, and the bodily expression of her current emotional state similarly work to ground the novella. As a result, trauma is written into the body after all, coinciding with and emphasized by that written into the land—and then into Rita’s art. At one point, in a scene where Rita tries to decipher whether a cryptic threat from a local is a microaggression, Morris crystallizes this for readers: “[t]here it was—that hitch in her chest like blazing terror, that feeling she sometimes thought of as inspiration. Maybe that violence was something she could deal with in her paintings.” The emphasis on painting suffuses the color palette of the prose, akin to how the green (a recurring motif, unsurprisingly) verdancy of the natural world colonizes everything: “Yellow melted to nothing, blue dissolved into sky, and the red work of death was done, instead, in the dizzying, hissing spectrum of green.” Arguably, the novella could be read very fruitfully in conversation with T.E.D. Klein’s “The Events at Poroth Farm,” as differing approaches to the weight of history bearing on isolated creative work in a weird place—but that’s a thought experiment for another day.

Rita’s newly inspired weird paintings stand in stark contrast to her earlier, naturalist landscape work, and this fecundity underlies the natural world of the swamp as well. Rita comes to accept that “you, too, are nature, and nature loves above all else transmutation, and impermanence, and creation.” However, Morris reminds us that even nature suffers under the settler-colonial trauma of climate change. Just as Rita’s personal losses haunt—colonize—her body and mind, climate change suffuses the world. Throughout the book, the two are linked, Rita’s dissolution and that of her people’s ancestral lands in the swamp, and Morris’s fiction refuses to flinch away from this tragic reality, that “[s]he and the land were two flailing fish on a drying shore.” Even her link with Mi’kmaq is trouble—a language she could never quite master, a side of her family she was never quite integrated with, and one of the many tense dualisms pervading the novella: Mi’kmaq/English, body/mind, city/country, science/nature, predator/prey.

Green Fuse Burning quickly turns from an initial explosion of weirdness on Rita’s first night to a lengthy character study wonderfully grounding the later horror that moves the novella into the realm of the numinous. Initially, I was quite thrown by the ending, an unexpected shift from what came before. On reflection, though, the novella is telling me exactly why it ends the way it does, and if this isn’t the ending I expected (or wanted, although that feeling is diminishing), who cares? It doesn’t diminish the power or beauty of what came before. It’s transformative, and transcendent, and maybe that’s what trauma and grief require—in our selves and our relationship with the land, in a world suffused with “a green that was alive and dead all at once, a green that smelled of both rot and new life, a green that beckoned and choked.”

Zachary Gillan (he/him) is a critic of weird fiction residing in Durham, North Carolina, USA. He’s an editor at Ancillary Review of Books, the book reviewer for Seize the Press, and has criticism in or forthcoming from Strange Horizons, Broken Antler, Interzone Digital, and Nightmare Magazine, among others. More of his work can be found here.