A Review of Joe Steinhardt and Marissa Paternoster’s Merriment

By Riah Hopkins

Fans of the (now disbanded) New Jersey punk trio Screaming Females are likely already familiar with lead singer/guitarist’s Marissa Paternoster’s art. Her illustrations—called “disturbing” by some, an exemplar of raw punk aesthetics by others—adorn Screaming Females’ album covers, t-shirts, and posters. And now, Paternoster’s illustrations can be found, too, in her debut graphic novel Merriment—a project created in partnership with Don Giovanni Records founder and writer Joe Steinhardt (Why to Resist Streaming Music & How). This, however, is not Paternoster’s first venture into comics. Short form, autobiographical comics published on Paternoster’s personal website tell stories about her adolescence—discovering identity in music, first forays into drugs and alcohol, and navigating that seemingly endless liminal space between childhood and adulthood. In Merriment, Steinhardt and Paternoster move to a new liminal space: the second adolescences of thirty-something adults waiting to become adults, to feel like and grow into their ages. Accordingly, the rather ironically titled Merriment is a novel that sees those of us who have inhabited (or are inhabiting) that second adolescence, and understands the unique humiliation and self-loathing that comes with watching everyone else get their act together while you’re still living in your childhood bedroom.

The story’s protagonist, Mack, understands these challenges all too well, having recently moved back into her mom’s house herself. She’s also unemployed, newly single, and in desperate search for a lifeline back to New York City—whether it be a job or a new romance. Until then, Mack kills time drinking beer and shooting the shit with her best friend, Denise. Together, the two of them go to lame house parties and grab coffee with the same friend group they’ve had since middle school. In these spaces, their conversations don’t seem to move much further than, “I wonder what so-and-so is up to now?”

Cover art by Marissa Paternoster.

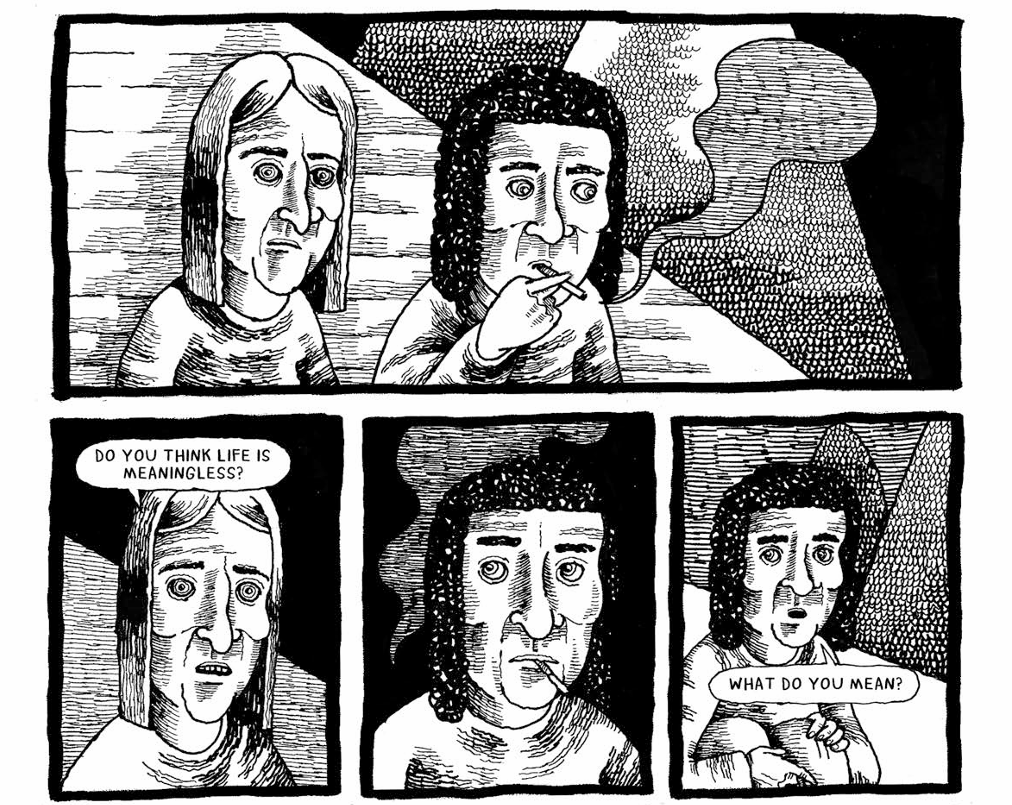

Capturing the comfortable—also deadening—repetition of living at home is one of the things Merriment does most successfully. The novel is equal parts humorous and heartbreaking. And this is due, in part, to Paternoster’s one-of-a-kind art style, a style that she has said is influenced by Philip Guston, Raymond Pettibon, and Ren & Stimpy. Consider Paternoster’s humans, for instance. They might be described as distorted creatures, with their sunken features and globular eyeballs—but they also capture the honesty of the situation better than any photograph ever could. Some of her characters have uncomfortable grins. Many have mouths that are more like voids, filled but not, with much too-small teeth. Others have drooping noses, cheekbones sans the underlying bone. In fact, gravity seems to be pulling many of Paternoster’s people down. And yet, even as Merriment’s characters appear visually grotesque, there is a beautiful frankness to such ugly. There is an authenticity and intimacy rendered in Paternoster’s linework that pulls the reader in close and lets them know that this is not a story concerned with the artificiality of beauty. This is a story concerned with what is real and underneath. Paternoster’s gnarled humans—whether they’re hugging their coffee cups, or gathering at boring parties, or spouting self-important nonsense like “I barely notice the art anymore. I only go to the museum to look at the frames at this point”—are absurdly good at illustrating these truths and bringing them to the surface. The novel’s more vulnerable moments, too, are often both tender and upsetting, emphasized even further through Paternoster’s art. Like when Mack and her mother tussle over a Mickey Mouse plush doll from a long ago vacation. In this moment, Mack insists upon throwing the doll away, calling it trash, while her mother fights to keep this remnant of a happy memory safe. In the end, Mack relents, handing the stuffed toy over to her mother. But the image that Mack’s rebuking words leave us with? These are cutting: “You do realize that I am still going to have to be the one that throws it away eventually?”

Used by permission from Merriment (Don Giovanni Records 2024). Copyright © 2024 by Joe Steinhardt & Marissa Paternoster.

That’s the thing though, about moving back into your childhood bedroom, about hanging out with friends who only talk about high school, about watching everyone else grow up, get married, and start their lives while you remain stagnant—you begin to feel like you have already done everything you were meant to do in life. You begin to feel like the only new thing left for you to experience is ceasing to live altogether. As Mack cycles through coffee get-togethers, parties with the same old people, and rooftop heart-to-hearts with Denise, she sinks deeper and deeper into this line of thinking, into these lines of thought that aren’t too far off from scarred-over yet continually scarring cuts themselves—never healing, still bleeding. Is happiness, she wonders, possible? Or is everyone faking it? How do we know that the world we interact with—the money we exchange, the ground beneath our feet, the people we love—really exists? “Imagine if I just cut into myself with a knife and there was nothing there,” Mack says to Denise, who tries to assure Mack that she is real. “I won’t do it,” Mack responds, “But how would I know?”

Back home, back in the spaces where Mack developed, she also seems to lose herself, to become a missing person, too. Not incidentally, missing person posters are also peppered throughout Merriment’s backgrounds. In the coffee shop, stapled to telephone poles, on the news—Mack is constantly reminded of literal loss, alongside the internal losses she feels. And, as Mack’s depression worsens, she begins to wonder if she is responsible for the woman’s disappearance, and possibly her death. For a moment, Merriment tricks the reader into believing that the narrative is going to take a more sensational turn, become a story about whether or not Mack really has killed the missing person. Yet, it doesn’t, in the end. Rather, the missing person acts as an intersecting narrative to Mack’s more interior one, and effectively places emphasis on mental health in a story about how to navigate life when you feel like life isn’t worth living.

Merriment, too, is a novel about change: the limerent wish for positive change, resisting change when it is not desired, and learning how to accept change—or the bleak absence of it—in your life. The novel doesn’t try to feed the reader a neatly packaged ending where a new love whisks Mack back to the city. Mack’s desires are not nicely wrapped and handed to her, complete with a bow. Nor are readers given an ending where Mack learns to be happy no! matter! what! What the character does learn, however, is that she’s not as stuck as she thinks she is. Mack’s fate is open ended, punctuated by her friend Liz’s advice that “doing nothing [with your life] means you could still do anything.” Fans of Paternoster’s music might find a connection to the illustrator’s own life in this messaging as well. Screaming Females (which was active from 2005-2023) may be defunct, but Paternoster can now do anything—like devote time to her solo music project, Noun, or venture into the world of graphic novels, or read this review and smile (with regular size teeth, thank you), or go out and create another stellar collaboration—like Merriment by Steinhardt and Paternoster truly is.

Riah Hopkins is a Rhode Island transplant to the Midwest, where she studies and teaches at the University of South Dakota. When she’s not reading or writing for Broken Antler, you can find her posting pictures of her evil bunny, Otto, @riah_0_hop.